|

| August 13, 2013 | Volume 09 Issue 30 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

3D-printing update:

Stratasys acquires MakerBot and venture capitalists discover key to 3D-printing money; Is home 3D printing really safe?

By Dr. Wendy Kneissl, Senior Technology Analyst, IDTechEx

By Dr. Wendy Kneissl, Senior Technology Analyst, IDTechEx

Stratasys, global giant of industrial 3D printing, announced on June 19 that it was to acquire MakerBot, the New York-based privately held manufacturer of desktop 3D printers. No surprise there you might think, although the Stratasys shareholders may have been a little taken aback by the price.

MakerBot was founded in 2009 with an aim to develop cheap, open-sourced, 3D printers based on Stratasys' own fused deposition modeling (FDM) technology that had at that time just come off patent. Having gained approximately $13 million in VC funding in 2011, however, the company took a slightly more ruthless approach and became closed source, losing many of its hitherto loyal adherents in the process.

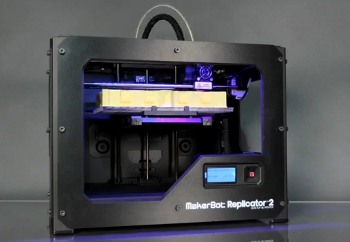

The MakerBot Replicator 2 desktop printer. [Image: Screenshot from MakerBot video]

Its Replicator series of 3D printers sell for around $2,000 to $3,000, a price point similar to the FDM-based Cubify printers of Stratasys' main competitor, 3D Systems, whilst the lowest priced printer currently marketed by Stratasys itself, the Mojo, currently comes in at a comparatively high $10,000.

The deal

And the deal with Stratasys? This stock-for-stock transaction sees MakerBot's shareholders receiving an upfront payment of 4.76 million new issue shares (currently valued at around $406 million) plus 2.38 million further shares by end-2014 if performance targets are met (current value around $201 million).

Whilst the deal cannot be precisely priced, not least as MakerBot shareholders cannot sell their newly acquired Stratasys shares for three months after closure and share prices of the 3D printer OEMs are historically volatile, the VCs look set to recoup in excess of $600 million on their initial $13 million investment in just two short years. With MakerBots' revenues for 2012 placed at $15.7 million, Stratasys shareholders are potentially paying a whopping 38x revenues to complete the acquisition.

So the obvious questions: What exactly are they acquiring and why didn't Stratasys, the world leader in FDM, simply develop its own desktop model?

MakerBot owns little proprietary technology and has no established network of resellers, relying instead on on-line sales. What it does have is a brand name and experience in the consumer 3D printing market to which Stratasys has come very late. To have paid the price it has, the Stratasys board must have been extremely determined to play catch up very quickly and to repair the damage MakerBot was seen to have done to sales at the lower end of its 3D-printer range. It hasn't only gained a brand, it has lost a competitor, and the companies will presumably now align their marketing strategies to avoid overlap where possible.

No doubt the fear that 3D Systems -- the monarch of acquisitions in 3D printing -- would itself have acquired MakerBot, forming a virtual monopoly in the consumer space, would have placed MakerBot in a very strong negotiating position. Stratasys must have feared such a marriage.

Where to now?

With access to the resources available through Stratasys, including a veritable smorgasbord of patents, MakerBot has the opportunity to bring the price of its printers down more quickly. With the company currently, however, maintaining its mammoth share of the consumer market against even lower priced consumer printers, this is unlikely to happen in the short term. Such a move would likely result in a loss of revenues.

Potential customers may be holding their respective breaths in the hope that the acquisition will spark a price war with 3D Systems, but this too is unlikely to happen. Neither Stratasys nor 3D Systems have an interest in hurting the sales of their more expensive printers for the sake of gaining share in what is currently a small consumer market.

In the longer term, however, it could be that Stratasys will follow the business model of the 2D-printer companies. Whilst the MakerBot plastic filaments (the 3D equivalent of 2D ink) are not currently proprietary, they could be made so, potentially leading to very cheap 3D printers using very expensive materials. For this model to work, however, would require a mass consumer demand for 3D printers for which there is frankly scant evidence. There are, in fact, already indications that growth in the relatively embryonic consumer market is slowing down.

In short, Stratasys has taken a gamble here. The future of the consumer market is unclear, and the barriers to entry are low. The company may have paid a very high price for a quick foothold in an ultimately relatively small market with an increasing number of competitors.

If MakerBot has sold out to the big corporate world in merging with Stratasys, as some of its former open-source adherents believe, it got a jolly good price indeed.

But are home desktop 3D printers safe?

Engineering readers may have noticed in the last couple of weeks a spike of Web articles concerning a paper, titled "Ultrafine particle emissions from desktop 3D printers" and authored by the Institute of Technology in Chicago and the National Institute of Applied Sciences in Lyon, relating to emissions from desktop 3D printers.

In short, the paper states that plastic fumes are not good for one's health.

It should first of all be noted that this ultimate conclusion is not really news. Many governments have, for many years hence, issued health and safety guidelines relating to plastic fume exposure in the workplace, as the latter are already known to be harmful. It was really only a matter of time before either regulation or a class-action law suit was going to catch up with companies selling printer models that fill homes with noxious gases -- a point already discussed in the IDTechEx report "3D Printing 2013-2025: Technologies, Markets, Players"

It should also be noted that the same hazard does not apply to the professional- and production-grade 3D printers employing thermoplastic extrusion, as these operate in an enclosed environment and do not therefore release fumes into the atmosphere.

That said, the potential danger associated to certain, more basic models is undeniable.

So should the hobbyist market lay down and die? I would respond with a resounding "no."

This is an opportunity, a real opportunity, for a company, inventor, or otherwise entrepreneurial person to develop a solution. Filters have been employed for decades in the power industries to remove toxic components from fumes (which is why we no longer suffer from the effects of acid rain), and there are a plethora of organizations selling nanoparticle membrane technologies that trap very small particulates that could potentially be adapted for 3D printers.

A filter or membrane that could be retrofitted to personal 3D printers would have a ready-made market. Sure, this would push the price up, but at what price is health?

In the meantime, a less high-tech solution is, of course, to open all the windows and leave the house.

For more information on 3D printing, read "3D Printing 2013-2025: Technologies, Markets, Players."

Published August 2013

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy